Striking a perfect ending is a difficult task at the best of times, but it is a challenge that is particularly complex for war movies. Having to juggle giving the central characters a resolution that feels justified while addressing the major themes of the movie can be a treacherous ordeal. Anything too triumphant dilutes the integral message that war is futile, and yet a relentlessly bleak finale can diminish all notions of humanity the film sought to explore.

All that being said, these 10 movies stick the landing with aplomb. Some of these films do opt for tragic endings that illustrate and emphasize their anti-war stances with poignancy and precision. Others maintain a sense of hope and humanity in their closing scenes, a flicker of goodness and grace amid a tapestry of the horrors of war. All of them excel at evoking powerful emotional responses that complement their thematic heft with consideration and composure, making them the best and most unforgettable endings war cinema has seen.

9

‘Saving Private Ryan’ (1998)

Directed by Steven Spielberg

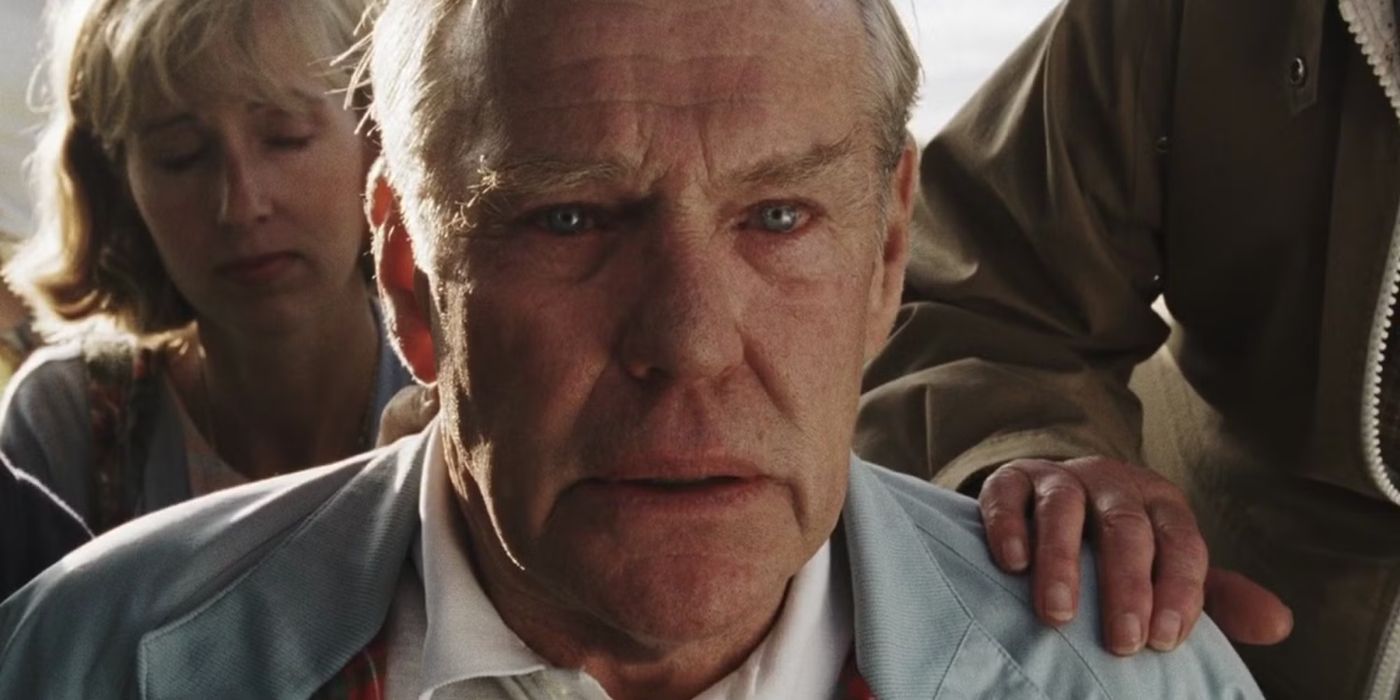

Perhaps the best-known war film of all time, Saving Private Ryan is an epic as awe-inspiring as it is confronting, with its story following a unit of American soldiers tasked with finding Private James Ryan (Matt Damon)—whose three other brothers have been killed in the war—so he can return to his family. It is a monumental trek through the carnage and chaos of the European Theater of WWII, one that culminates in a brutal battle in Ramelle where Captain Miller’s (Tom Hanks) squad stands with Ryan’s ragtag outfit. As Miller succumbs to his wounds, he tells Ryan to “earn this” before the film leaps ahead in time to an elderly Ryan at a military cemetery with his family.

In isolation, it is a piercing conclusion that comments on the futility and waste of war without ever calling into question the heroism and legacy of those who sacrifice their lives on the front lines. In another sense, the “earn this” line is directed more to the audience, with Steven Spielberg imploring viewers to acknowledge all those who die in war and to ensure they live their lives in a manner that honors that sacrifice.

8

‘Grave of the Fireflies’ (1988)

Directed by Isao Takahata

One of the sharpest and most decisive anti-war films ever made, Grave of the Fireflies is a beautiful yet heartbreaking tale of love and desperation during war time. It follows a teenage boy and his little sister as, after the death of their mother during an air raid, they are forced to move to the countryside. Struggling to find enough food and banished to live in a cave, Seita’s (Tsutomu Tatsumi) tireless efforts to provide for his sister come to a tragic end when she dies from malnutrition. He dies weeks later.

It is a devastating story that illustrates the heinous impact war has on civilians with unrestrained emotional might. However, the underlying story of Seita’s and Setsuko’s (Ayano Shiraishi) souls comes to a beautiful conclusion as they sit overlooking present-day Kobe—their hometown—as fireflies abound. Not only visually gorgeous, it is a testament to humanity’s resolute endeavor to rebuild, but one that never loses sight of what the Japanese were rebuilding from. Hopeful and haunting at once, it complements the brilliance of Grave of the Fireflies by the siblings a splash of the happiness and peace they deserved without ever relenting on its convictions of war.

7

‘The Grand Illusion’ (1937)

Directed by Jean Renoir

One of the oldest classics of the genre, The Grand Illusion is as sophisticated and elegant yet insightful a look at war and its impact on notions of camaraderie and society as has ever been released. With a story following a small group of French POWs, including an aristocratic captain who forms an intellectual bond with a German nobleman in charge of one of the camps, it delves deep into concepts of class, wealth, elitism, and how those ideas stand in an era of upending change as war spreads around the globe.

The ending is relatively simple. Two of the POWs escape Germany into the snow-swept neutral zone that is Switzerland, finally free from Nazi pursuit. In a storytelling sense, it is a peaceful, welcome conclusion. Where it finds its greatness, however, is in a metaphorical sense. The film is ultimately about how oppressive class systems in Europe would rapidly grow outdated as societal shifts unfurl violently as a result of the First World War. Presented as a wide shot from afar, the film’s closing represents a progression towards a new world of unknown challenges.

Grand Illusion

- Release Date

-

September 12, 1937

- Runtime

-

113 Minutes

-

Jean Gabin

Le lieutenant Maréchal

-

Pierre Fresnay

Le capitaine de Boëldieu

-

Erich von Stroheim

Le capitaine von Rauffenstein

-

6

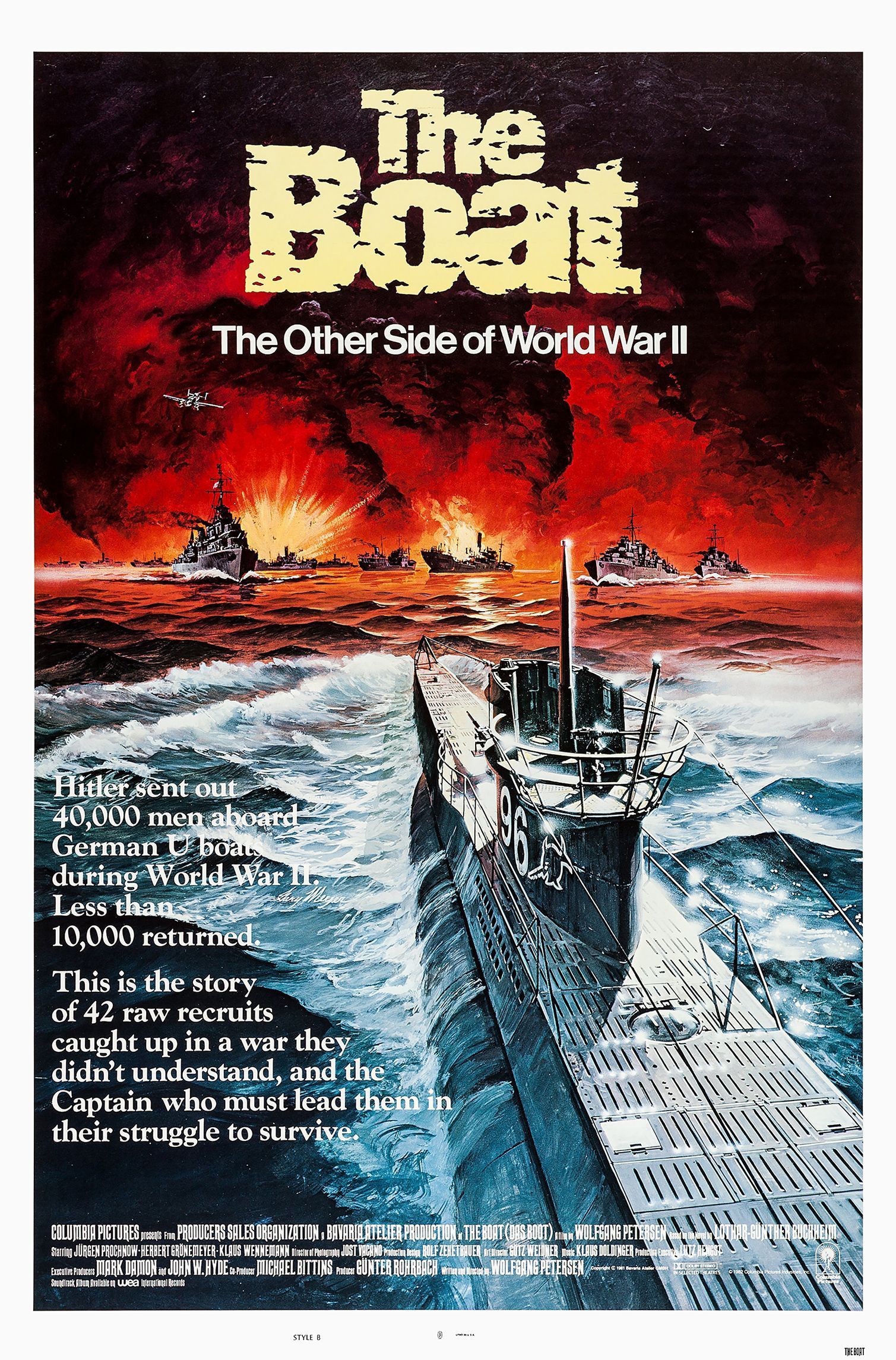

‘Das Boot’ (1981)

Directed by Wolfgang Petersen

A German film following the crew of a U-boat as they patrol the Atlantic Ocean, Das Boot opens with a blurb detailing the mass casualties such crews suffered over the course of the war. When the film premiered in America, the audience cheered this message emphatically. Their attitude changed somewhat through the course of the film. Not only does the military movie masterpiece delve into the unbearable claustrophobia and frightful intensity of life in a submarine, it also invests heavily in the men on the crew and the brotherhood they form, not to mention the logistical hardships they are forced to endure.

With the sub battered and badly damaged, the crew are forced to make for La Rochelle, with the film ending on their arrival, greeted by a small welcoming party. The celebrations are short-lived, however, as an RAF air raid bombards the dock leaving many dead and wounded. It is a bleak and damning conclusion, one that sees the film use its own humanity to deliver a poignant commentary on the futility of war.

Das Boot

- Release Date

-

September 17, 1981

- Runtime

-

149 Minutes

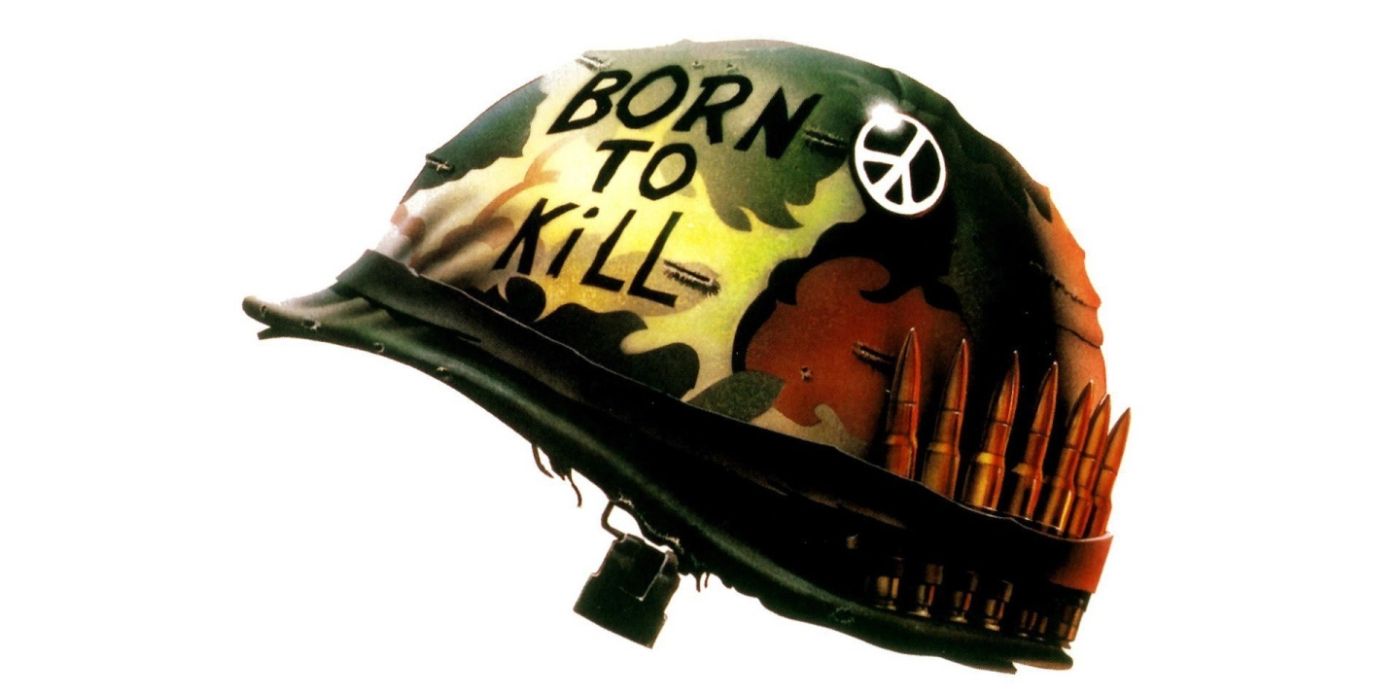

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

Full Metal Jacket concludes with a uniquely piercing ending. Private Joker’s (Matthew Modine) battalion marches past the decimated and flaming ruins of a Vietnamese city singing the “Mickey Mouse March” while Joker’s narration recalls his salacious, juvenile fantasies and his happiness that he is alive, even in such a world. It’s the devastation of war laid bare and the innocence and immaturity of soldiers not far removed from adolescence illustrated in tandem to captivating, albeit disturbing effect.

It is a perfect ending to what is one of the more challenging films based on the Vietnam War, with the Stanley Kubrick classic eager to emphasize how soldiers are dehumanized through their training regimes, the psychological strain of combat, and the innocence that is lost when young men are thrust into war. In essence, Full Metal Jacket’s final scene encapsulates the film’s themes in grueling, grim, and even darkly comical fashion, delivering an appropriately unsettling conclusion to what is one of the most intense war movies ever made.

4

‘Life is Beautiful’ (1997)

Directed by Roberto Benigni

As hopeful as it is heartbreaking, Life is Beautiful is a picture of profound humanity set amid one of the most horrific chapters in human history. It follows Italian jew Guido (Roberto Benigni) as he and his family are sent to a Nazi concentration camp. Striving to shield his young son from the horrors surrounding them, he uses comedic antics, willpower, and his unbridled imagination as he tells the boy that they are actually in the midst of a competition and that they must follow all the rules to win the grand prize, a tank.

The final ten minutes of the movie are a masterpiece of emotional contrast, as Guido’s unwavering love for his son culminates in a heart-wrenching act of sacrifice. The following morning, young Giosué (Giorgio Cantarini) emerges from his hiding place just as a U.S. Army unit—led by a tank—arrives to liberate the camp. While traveling to safety, Giosué spots his mother, with the film ending as the two are united. It makes for a life-affirming though tragic testament to the human spirit, one that champions the preservation of childhood innocence and commemorates the sacrifices made in times of war.

3

‘The Great Dictator’ (1940)

Directed by Charlie Chaplin

There is a certain peculiarity in the notion that Charlie Chaplin—an icon of the silent era—delivered one of the greatest and most timeless speeches to have ever graced the silver screen. That came at the conclusion of The Great Dictator, a daring satire that lampooned the tyranny of Adolf Hitler. It sees Chaplin star in dual roles as the dictator of Tomainia, Adenoid Hynkel, and as an amnesiac Jewish barber living in the ghetto who becomes embroiled in a resistance movement.

Using the physical resemblance to their advantage, the resistance manages to supplant Hynkel with the barber, only for him to have to address the nation so as not to blow his cover. Going for about four minutes, his speech comments on the futility of war and the hardening nature of social values by appealing to notions of humanity and happiness. It transcends the film’s comedic tone and addresses the audience directly, leaving an indelible mark with its power and poignancy that has seen it remain relevant for decades.

2

‘Paths of Glory’ (1957)

Directed by Stanley Kubrick

One of the most poignant and provocative anti-war films ever made, Paths of Glory is a searing indictment on military malpractice. Set during WWI, it transpires as three French soldiers are picked out to be charged with cowardice following their battalion’s refusal to carry on with a futile and suicidal advance on enemy territory. They are represented by Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas), their commanding officer, who is a criminal defense lawyer in civilian life, though he fears the outcome of the trial may be predetermined.

It is a callous and cold observation of wartime philosophy, one that sharpens its convictions on the futility of war with themes of corruption within army hierarchies and the abuse of power. The film ends on a far more humane note, however, with a young German woman singing to a room full of French soldiers who are moved to tears. Amid the dehumanizing brutality of war, it is a moment of shared humanity that proves the basic capacity for empathy and connection remains.

1

‘All Quiet on the Western Front’ (1930)

Directed by Lewis Mileston

Despite the fact that it is nearly 100 years old, All Quiet on the Western Front remains one of the greatest and most poignant war movies ever made. Adapted from Erich Maria Remarque’s semi-autobiographical novel, it follows Paul Bäumer (Lew Ayres) and his classmates as, seduced by the promise of glory and adventure, they enlist to fight in WWI. The group are confronted by disillusionment when they make it to the front lines and are confronted by the unflinching brutality of combat in the trenches.

The film’s ending is faultlessly bleak, with Paul, devastated by the recent death of his friend, momentarily transfixed by the beauty of a butterfly hovering just outside his fortification and tries to reach out to grab it, only to be gunned down by an enemy sniper. Concluding with Paul and his classmates’ arrival on the Western Front superimposed over images of a veterans’ cemetery, All Quiet on the Western Front closes on a somber note of innocence and devastation that has made it one of the most powerful films the genre has seen.

NEXT: The 55 Best War Movies of All Times, Ranked