The spaghetti Western was more than just an Italian imitation. It was a reinvention. Where classic American Westerns of the late 1950s and early ’60s leaned on clean-cut heroes and moral clarity, their Italian cousins gave us grit, greed, and a world where even the good guys had blood on their hands.

They were violent, stylish, and often political. Their landscapes were vast, their morality was murky, and their music, thanks to maestros like Ennio Morricone, was pure fire. With this in mind, here are 10 essential spaghetti Westerns that defined a subgenre and redefined cool.

10

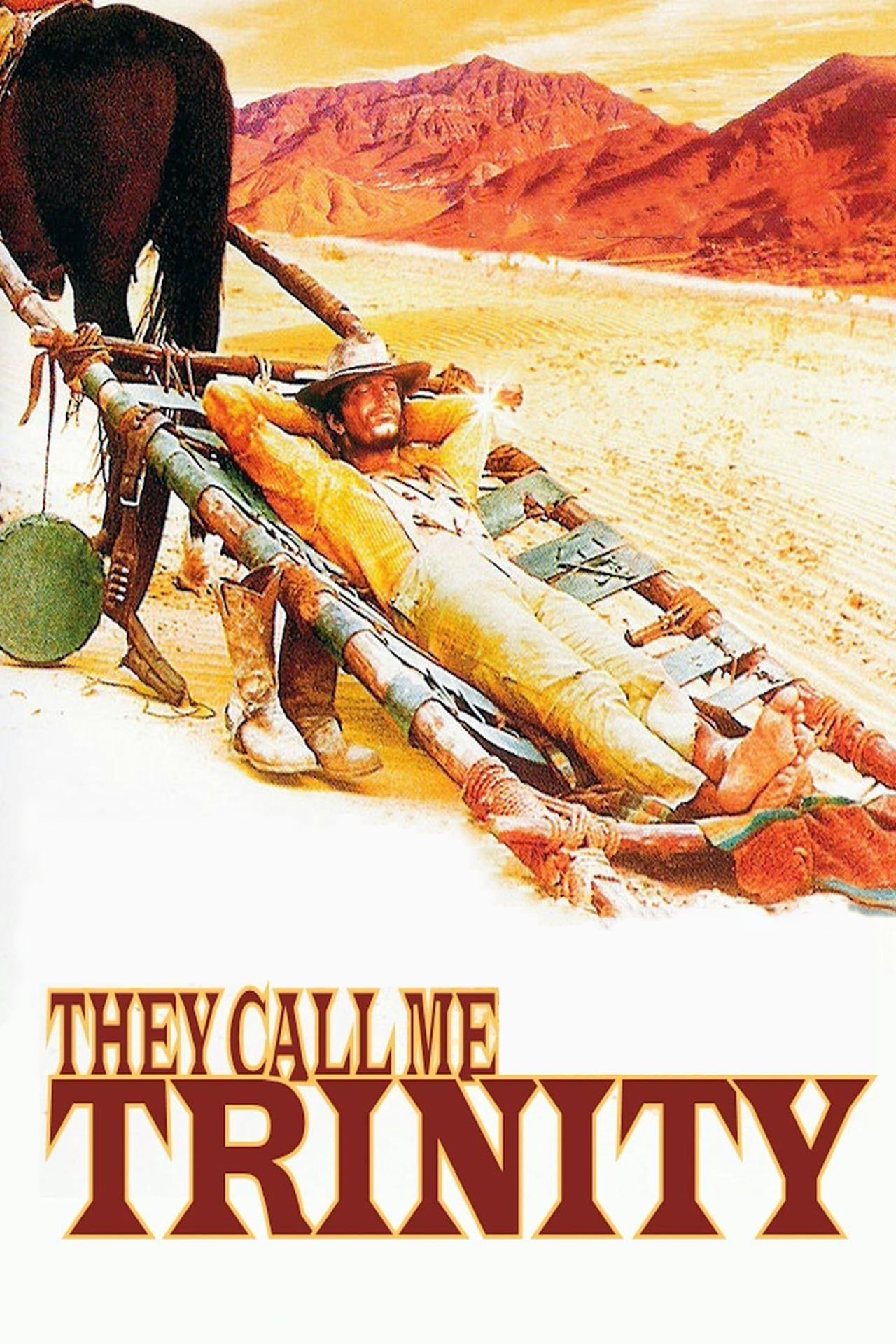

‘They Call Me Trinity’ (1970)

Directed by Enzo Barboni

“If you go on being greedy and unjust, someone much worse than me will punish you.” This isn’t your typical shootout-heavy spaghetti western. They Call Me Trinity took the grit and grime of the genre and flipped it into something playful, almost slapstick. Terence Hill turns in a humorous performance as Trinity, a lazy, lightning-fast gunslinger who’d rather nap than fight—unless you mess with his brother.

The film is full of physical gags, dry one-liners, and a weirdly sincere sweetness that balances out the fists and gunfire. Against all odds, it brings levity to a genre mostly built on death and revenge. And somehow, it still feels like a western. The dusty towns, the quickdraws, the moral ambiguity; it’s all here, just refracted through a much sillier lens. It’s proof that even the roughest genre has room for charm. Interesting bit of trivia: They Call Me Trinity‘s theme tune is used during the closing scene of Django Unchained.

They Call Me Trinity

- Release Date

-

December 22, 1970

- Runtime

-

115 Minutes

- Director

-

Enzo Barboni

- Writers

-

Enzo Barboni

9

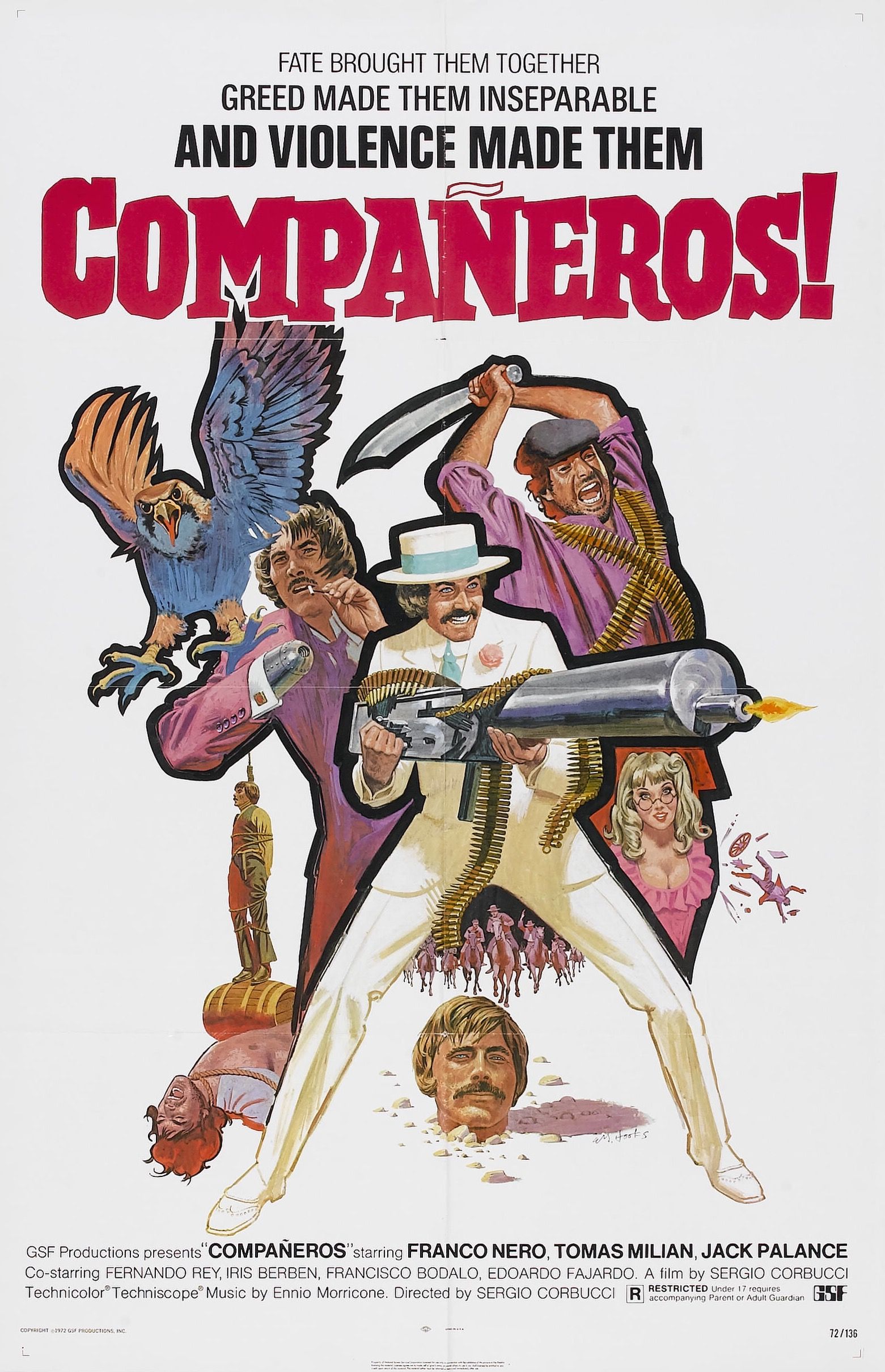

‘Compañeros’ (1970)

Directed by Sergio Corbucci

“I don’t trust a man who won’t drink. People who don’t drink are afraid of revealing themselves.” Compañeros blends revolution, friendship, and betrayal into a wild ride of a western. Franco Nero plays a suave Swedish arms dealer, while Tomas Milian‘s rebel bandit brings grime and chaos to the screen. Together, they stumble through a mission to rescue a pacifist professor, while trying not to kill each other first.

Sergio Corbucci, one of the genre’s giants, injects the film with political bite and dark humor. There’s action, sure (plenty of it), but also commentary on war, capitalism, and what freedom actually means. And then there’s Jack Palance as a one-handed, weed-smoking villain with a pet falcon. You don’t forget that kind of thing. It’s messy, stylish, and full of moral gray zones. The film wears its heart on its dusty sleeve, and the Morricone score ties it all together with a mix of swagger and sorrow.

Compañeros

- Release Date

-

March 31, 1972

- Runtime

-

115 Minutes

8

‘The Big Gundown’ (1966)

Directed by Sergio Sollima

“The best reason to kill is to have a reason.” The Big Gundown is a tense, cat-and-mouse chase through the Mexican desert, and it might be Lee Van Cleef‘s finest hour. He leads the cast as Corbett, a former bounty hunter turned politician. He sets out on one last mission to track down a wily Mexican peasant named Cuchillo (Tomas Milian), accused of a brutal crime. What starts as a simple pursuit turns into a layered, almost philosophical battle between justice and power.

Cuchillo is slippery and full of surprises, more folk hero than fugitive. Corbett, on the other hand, starts to question who he’s really serving. On the aesthetic side, Sergio Sollima crafts every scene with tension and purpose, and Morricone’s score—whistles, guitars, rising dread—is one of his most underrated. It’s a film about pursuit, but also about waking up to the truth that maybe the system you fight for isn’t fighting for you.

7

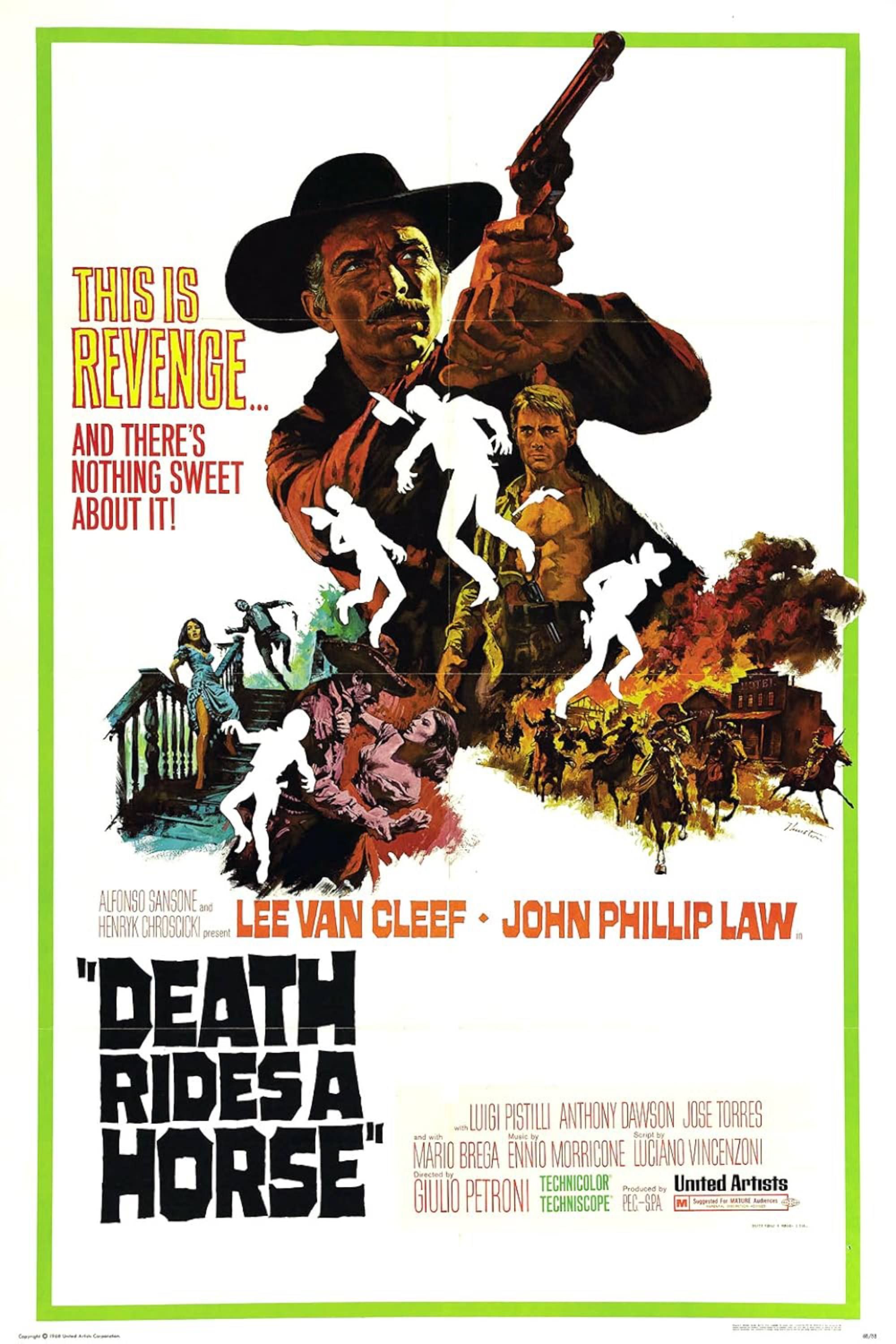

‘Death Rides a Horse’ (1967)

Directed by Giulio Petroni

“When you start killing, it is hard to stop.” Revenge runs red through this one. A young boy watches his family being slaughtered. Fifteen years later, he becomes a gunslinger (John Phillip Law) bent on vengeance. Sounds familiar, right? It’s classic western stuff: cold landscapes, colder men, and justice served through a rifle scope. But Death Rides a Horse does more than echo the genre’s main tropes; it sharpens them.

The flashbacks are stylized, the pacing deliberate, and the tension ever-rising. And the score? Morricone, again, delivering something eerie and pulsing. On the acting front, Law is solid as the fresh-faced avenger, but it’s Van Cleef, as the grizzled outlaw with his own score to settle, who steals every scene. Their uneasy alliance—sometimes partners, sometimes rivals—drives the film. It’s not the most famous movie in the subgenre, but it might be one of the most focused. Every bullet matters. Every stare means something.

Death Rides A Horse

- Release Date

-

August 31, 1967

- Runtime

-

114 Minutes

-

-

John Phillip Law

Bill Meceita

-

Mario Brega

Walcott’s Henchman in Waistcoat

-

6

‘A Bullet for the General’ (1967)

Directed by Damiano Damiani

“In a revolution, you shoot the enemy, not your own people.” This one doesn’t play coy. A Bullet for the General is overtly political, unapologetically revolutionary, and deeply cynical about who really profits from chaos. Set during the Mexican Revolution, it centers on El Chuncho (Gian Maria Volonté), a bandit-turned-rebel, and a mysterious gringo (Lou Castel) who may not be who he says he is.

Volonté plays Chuncho with wild-eyed charisma and volatility, flipping between joyful chaos and weary reflection. The dynamic between him and Castel’s character is what makes the film tick. Trust erodes slowly, until it explodes. The action is explosive, the politics razor-sharp. This is no mere exploitation flick: the script was penned by Franco Solinas, most well-known for writing The Battle of Algiers. Refreshingly, he and director Damiano Damiani include some serious reflections on Mexican history within this Western package. If Sergio Leone was the poet of the spaghetti western, Damiani was the polemicist.

5

‘The Great Silence’ (1968)

Directed by Sergio Corbucci

“I don’t like to see an unarmed man shot down.” Bleak, snowbound, and brutal, The Great Silence flips the genre on its head. Instead of dusty deserts, we get frozen wastelands. Instead of a wisecracking gunslinger, we get a mute avenger nicknamed Silence (Jean-Louis Trintignant). And instead of triumph, we get something much colder. The score, by Morricone, is haunting, almost funereal. And the villain performance by Klaus Kinski is genuinely unsettling.

If some of the shots in this one look familiar, it’s because Tarantino paid homage to them in both Django Unchained and The Hateful Eight. However, he doesn’t come close to achieving this movie’s cruel, chilling vibe. This is not a film that makes you cheer. The Great Silence makes you shiver. It’s arguably the bleakest spaghetti western ever made, which is saying something. Here, Corbucci doesn’t just question the myth of the Old West—he buries it under ice.

4

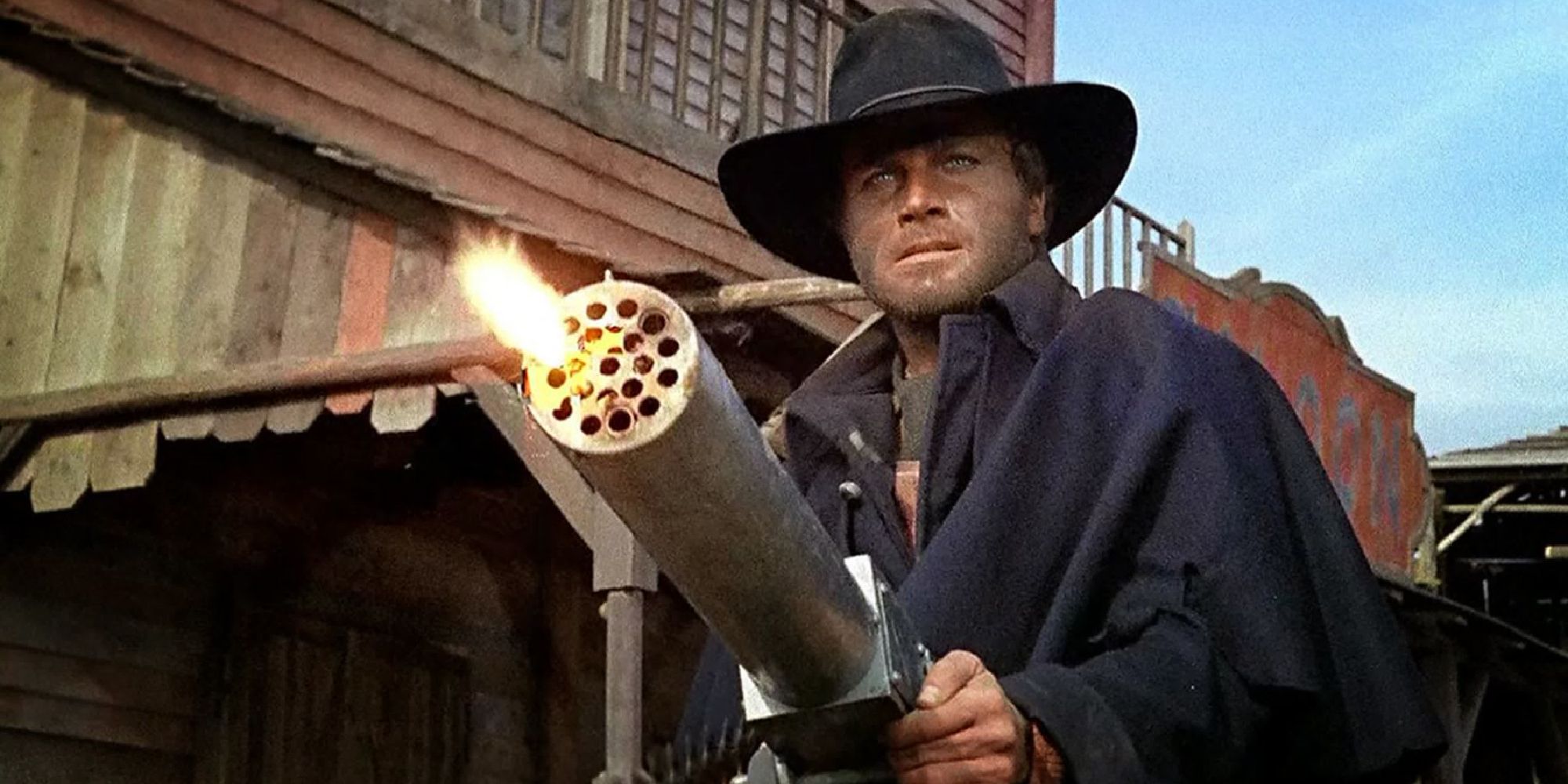

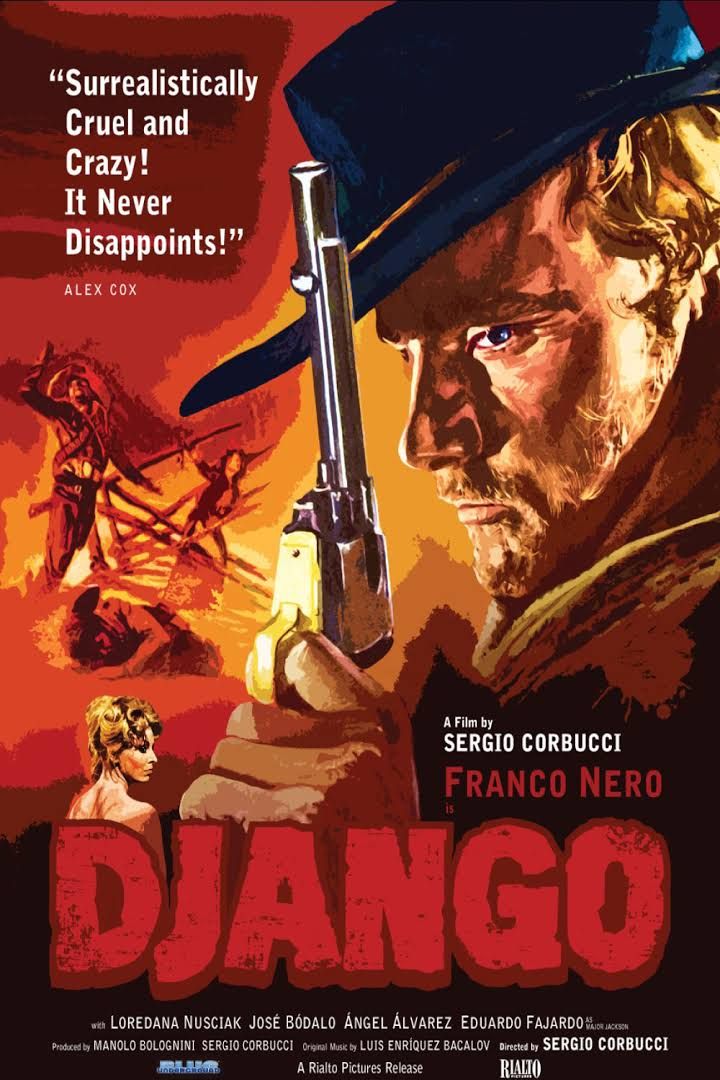

‘Django’ (1966)

Directed by Sergio Corbucci

“I never thought it would be you.” Before Tarantino rebranded him, Django was already a Western hero. Franco Nero plays the titular drifter, who walks into a border town with a machine gun, a grudge, and very few words. What follows is gritty, violent, and iconic as hell. The opening scene alone, Django dragging that coffin across a desolate landscape, is burned into cinematic history. And what’s in the coffin? Well, let’s just say it levels the playing field.

In general, Corbucci’s take on the western was more brutal than romantic. While not as harsh as The Great Silence, Django definitely still has a mean edge, not to mention a ton of violence. Bullets fly, and the body count is absurd. But Nero brings a strange nobility to the bloody mayhem. He’s not a hero, exactly, but he is justice in a world that barely remembers what the word means.

Django

- Release Date

-

November 30, 1966

- Runtime

-

91 Minutes

3

‘For a Few Dollars More’ (1965)

Directed by Sergio Leone

“When the chimes end, pick up your gun.” It might be a little boring, but any ranking of spaghetti Westerns has to end with some combination of Sergio Leone’s masterpieces. The second chapter in the Dollars Trilogy is more ambitious than the first and, in many ways, more personal. Clint Eastwood‘s Man with No Name is back, but this time he’s got company: Lee Van Cleef’s Colonel Mortimer, a rival bounty hunter with a score to settle and a pocketwatch that plays a haunting tune.

This is a movie that balances cold-blooded action with strange beauty. There’s revenge, sure, but there’s also grief, memory, and the kind of pain that doesn’t announce itself. For a Few Dollars More is not just about who’s fastest. It’s about why you draw. Mortimer, for example, isn’t just here to kill. He’s here to remember. Leone’s direction is sharp, his close-ups more electric than the gunfire. And Morricone’s score (Those chimes! That build-up!) is practically operatic.

2

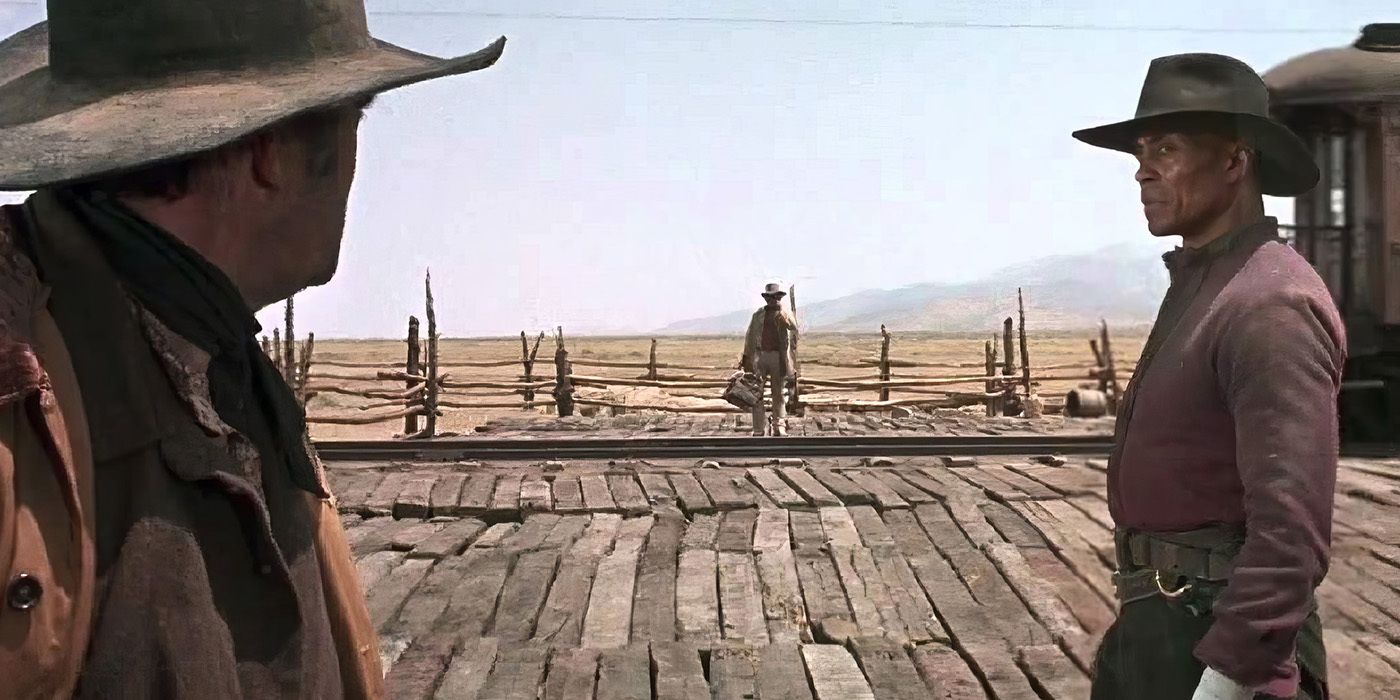

‘Once Upon a Time in the West’ (1968)

Directed by Sergio Leone

“You brought two too many.” This is Leone’s grandest project. Grand, mournful, and mythic, Once Upon a Time in the West feels like the Western to end all Westerns. Every frame is loaded. Every glance feels biblical. The story’s simple—railroads, revenge, and land—but the scale of it is operatic. Charles Bronson‘s Harmonica is the quiet protagonist, Henry Fonda plays gloriously against type as a sadistic killer, and Claudia Cardinale brings steel and soul to the heart of the film.

But it’s not just the cast. It’s the rhythm. Leone takes his time. Scenes breathe, particularly the legendary opening sequence. Tension coils. And when violence comes, it’s sudden and shattering. Morricone’s score might be the greatest ever written for a western: elegiac, eerie, unforgettable. Overall, this isn’t a film that rushes to a shootout. It sinks into one. Not for nothing, Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, and Vince Gilligan have all cited it as an influence.

1

‘The Good, the Bad and the Ugly’ (1966)

Directed by Sergio Leone

“When you have to shoot, shoot. Don’t talk.” The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is the genre’s full symphony: wild, funny, cruel, and absolutely iconic. Clint Eastwood, Lee Van Cleef, and Eli Wallach orbit each other in a Civil War-torn wasteland, chasing gold and dodging death. Eastwood’s Blondie is all squint and silence; Van Cleef’s Angel Eyes is ice wrapped in black; and Tuco, Wallach’s character, manages to be cowardly, cunning, and yet strangely lovable.

The three of them form a triangle of greed and survival, each outplaying the others until that legendary three-way standoff. Leone’s style is at full tilt here, replete with close-ups, wide shots, and long silences broken by sudden violence. Then there’s Morricone’s theme tune, a string of notes that are now synonymous with the whole genre. Ultimately, this isn’t just a great spaghetti western. It’s the blueprint. Every dusty road movie that came after owes it something. Probably everything.

NEXT: Kurt Russell Might Be His Generation’s Most Underappreciated Star, and These 10 Movies Prove It