The thriller is among the most atmospheric and haunting genres in cinema, to the point where levity is scarce and often non-existent. Indeed, thrillers aren’t known for their cheerfulness, but even by the standards of the genre, the movies on this list are dark. They don’t comfort you, they don’t offer justice; they leave you in silence, staring into the void, unsure whether anything good will ever happen again.

These thrillers are the bleakest of the bleak, stories where violence doesn’t redeem and where the bad guys don’t always get caught. Moral decay, corruption, lack of faith, and an overall sense of doom are all common themes in these pictures, but it’s all in service of a great story. Each of the films below is a masterclass in dread, some of them touching on fascinatingly grim philosophical ideas.

10

‘Prisoners’ (2013)

Directed by Denis Villeneuve

“Every day, she’s wondering why I’m not there to rescue her. Do you understand that? Me, not you. Not you, but me!” Prisoners marinates in despair. When two young girls vanish, their parents unravel. Hugh Jackman plays a father so desperate he turns to torture, convinced a quiet young man (Paul Dano) knows more than he says. Opposite him, Jake Gyllenhaal plays the detective trying to hold the center as everything else breaks.

Through these three men, Denis Villeneuve traps the entire film in a cold, gray purgatory, where hope curdles into obsession and good men do terrible things. There are no easy answers here; every lead hits a dead end, every moral line blurs. The cinematography, by Roger Deakins, feels almost haunted, like the world itself is mourning. And the final scene, a wordless cry from beneath the ground, lingers like a wound. For all these reasons, Prisoners is an endurance test for the characters and us.

9

‘Zodiac’ (2007)

Directed by David Fincher

“I need to know who he is. I need to stand there, I need to look him in the eye, and I need to know that it’s him.” Zodiac has no jump scares, no climactic chase, and no final confrontation with a killer. Instead, there’s just the slow spread of obsession. Spanning decades, the film charts the real-life investigation into the Zodiac Killer, who taunted police and the media with cryptic letters and was never caught. Here, David Fincher builds tension not from action, but from the awful weight of time, the way unanswered questions fester and grow.

All the main characters get caught up in the search, but Gyllenhaal’s cartoonist-turned-amateur-sleuth becomes truly consumed, sacrificing his marriage and his peace of mind for a truth that might not exist. No matter how hard he searches, the killer remains a shadow, always just out of reach. The horror comes not from what we don’t know, but from what we’ll never know.

8

‘The Vanishing’ (1988)

Directed by George Sluizer

“Where is she?” This Dutch masterpiece begins with a disappearance and ends with a soul-crushing revelation. A woman (Johanna ter Steege) vanishes at a rest stop, and her boyfriend (Gene Bervoets) searches obsessively. Years pass; the audience learns what happened, but he does not. This unusual expositional style and structure create an interesting tension. Still, the film’s real impact lies in its cold detachment: no flashy aesthetics, no music cues, no violence played for shock.

Eventually, the man meets the kidnapper (Bernard-Pierre Donnadieu), who calmly explains what he did and why. The boyfriend is given a choice: if he truly wants to know what happened to her, he must experience it himself. And he agrees. From here, the story veers into truly grim territory, and the final image is among the most gutting in cinema. In other words, The Vanishing is a horror movie in disguise, a psychological autopsy that slices without mercy.

7

‘Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer’ (1986)

Directed by John McNaughton

“It’s always the same and it’s always different.” Henry is not a cat-and-mouse thriller. There’s no detective on the killer’s tail. In fact, there isn’t a clear story arc at all. It’s just Henry (Michael Rooker), a soft-spoken drifter who kills without anger or pleasure, only vacancy. We follow him through seedy apartments and nameless alleys, watching him murder with chilling detachment. The violence is ugly, often implied rather than shown, but that only makes it worse.

We’re made to sit in the aftermath, watching TV over a corpse or tossing bodies in a river. Henry is less about crime than about the absence of meaning in a world where some people feel nothing at all. Worse still, this aspect of the movie was loosely inspired by real killers. The final scene, involving a suitcase and a quiet drive, may be the single bleakest ending of any serial killer film ever made.

6

‘Se7en’ (1995)

Directed by David Fincher

“What’s in the box?” Fincher strikes again. Se7en is structured like a detective story, but it ends as a sermon, a brutal, biblical condemnation of modern sin. Two cops (Brad Pitt and Morgan Freeman) chase a killer who stages grotesque murders based on the seven deadly sins. The crimes escalate, the killer turns himself in, and then comes the twist. The bleakness here is in the movie’s philosophy: Its central idea is that the world is broken, and trying to fix it only proves the point.

John Doe (Kevin Spacey) is the embodiment of this worldview, both villain and prophet. His plan is meticulous, and his final act, envy and wrath, turns Pitt’s character into both victim and accomplice. Se7en‘s final shot — a shattered man being driven away as Freeman quotes Hemingway — is pure despair. With scenes like this, Se7en doesn’t ask if evil can be defeated; it asks if it even matters, and then it leaves you there, in the rain.

5

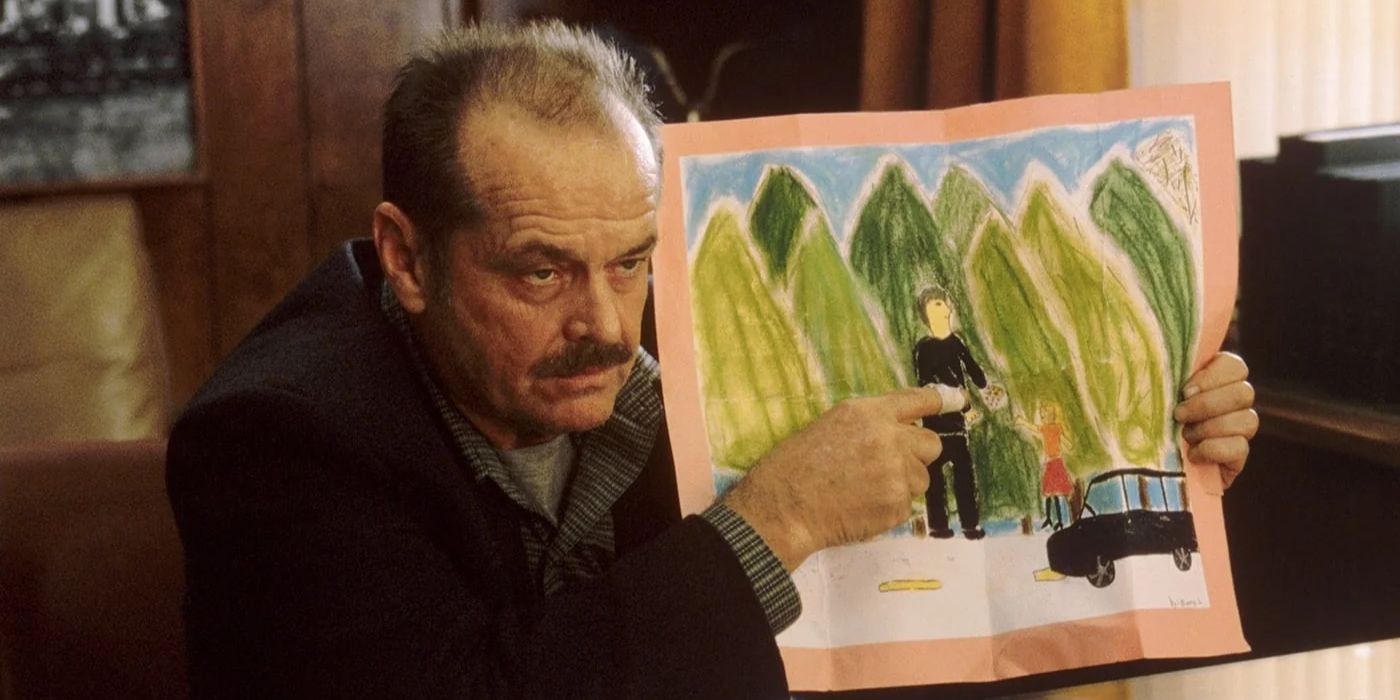

‘The Pledge’ (2001)

Directed by Sean Penn

“I made a promise. I made a promise.” With thematic parallels to Zodiac, The Pledge is about a detective who can’t let go of a case, even when he should. Jack Nicholson is Jerry Black, a retired cop who swears to a grieving mother he’ll find her daughter’s killer. But the deeper he dives, the further he drifts from reality. Jerry becomes convinced he’s found the killer and even uses a single mother and her child as bait, but the killer never comes, the trap never springs, and Jerry loses everything: His job, his love, his mind.

This is a film that dismantles the classic thriller arc and replaces resolution with ruin. Sean Penn directs everything with a deft, unsparing touch. The final scenes, in particular, are almost unbearable. They show a broken man muttering to himself in a gas station parking lot, abandoned by everyone. It adds up to one of the cruelest and most honest deconstructions of crime-fighting heroism ever filmed.

The Pledge

- Release Date

-

January 19, 2001

- Runtime

-

123 minutes

4

‘Nightcrawler’ (2014)

Directed by Dan Gilroy

“If it bleeds, it leads.” Nightcrawler shows us a world where ambition has no bottom. Gyllenhaal returns in a very different mode, turning in a chilling performance as Louis Bloom, a wide-eyed sociopath with a thousand-yard stare and an unnerving smile. He discovers that filming late-night crimes for local news is both profitable and thrilling. He gets the footage no one else can, because he has no shame. Lou manipulates scenes, stages accidents, and lets people die, all in pursuit of the perfect shot.

Worse still, this plan works out well for him. The movie ends not in Lou’s comeuppance but his promotion. Thematically, Nightcrawler is pitch black, showing us the news cycle as a meat grinder where suffering becomes content. In this world, monsters don’t hide; they build brands. These ideas arguably resonate even more today than they did on release. Now, politicians and pundits everywhere are turning real pain into fodder for their ambitions and profit.

3

‘Wind River’ (2017)

Directed by Taylor Sheridan

“This is the land of you’re on your own.” One of Taylor Sheridan‘s stronger efforts, Wind River is a murder mystery set on a frozen Native American reservation. Though it’s cloaked in crime thriller garb, it’s really a statement on grief. When a young Indigenous woman is found dead in the snow, a wildlife tracker (Jeremy Renner) and an FBI agent (Elizabeth Olsen) begin to unravel the truth. What they find is not a twist, but a confirmation: that this land is indifferent, brutal, and forgotten.

Every frame along the way radiates sorrow, showing us an entire community erased by history and neglect. The violence is shocking, but never gratuitous. The killers are not masterminds, just cowards enabled by silence. The final confrontation is cathartic in its rage, but not triumphant. Sheridan ends the film with a quiet, devastating title card: that no one keeps track of missing Indigenous women. The crime may be solved, but the system remains broken.

2

‘The Silence of the Lambs’ (1991)

Directed by Jonathan Demme

“You think if Catherine lives, you won’t wake up in the dark ever again to that awful screaming of the lambs?” The Silence of the Lambs is anchored by two predators, one in a cage, the other at large. Clarice Starling (Jodie Foster), a young FBI trainee, is pulled into a psychological labyrinth when she’s asked to consult with Dr. Hannibal Lecter (Anthony Hopkins). What begins as a search for Buffalo Bill (Ted Levine) becomes a descent into her past, fears, and vulnerabilities.

This movie brought the genre to new heights, adding layered and believable characters to its compelling plot. Clarice is brilliant, brave, and determined, but she’s also alone, repeatedly minimized, objectified, and underestimated. Lecter toys with her mind, while Bill prepares to skin another victim. And though Clarice does save the girl, the ending doesn’t feel victorious. Lecter walks free, the system still feels warped, and the silence hasn’t truly lifted.

1

‘No Country for Old Men’ (2007)

Directed by Joel and Ethan Coen

“You can’t stop what’s coming.” No Country for Old Men is about a man (Josh Brolin) who finds drug money in the desert and the unstoppable killer who comes after him. But that’s just the surface. Filtering Cormac McCarthy through the Coen brothers‘ sui generis perspective, the film’s true subject is the death of meaning in a world where chaos wins. More than a villain, Javier Bardem‘s Anton Chigurh is entropy in human form, killing without passion, flipping coins to decide fate.

Tommy Lee Jones, meanwhile, plays a sheriff too old, too tired, and too decent for what the world has become. His story doesn’t end with a final shootout or justice done. The main character dies offscreen, and the sheriff retires with a sigh. Then the film ends on a dream, one about his father, a light in the dark, long gone. It’s all profoundly sad. The future, No Country for Old Men says, doesn’t care about us.

NEXT: These 10 Movies Have the Best First 5 Minutes in Cinematic History